Managing to Learn: Using the A3 Management Process

Managing to Learn: Using the A3 Management Process

by John Shook

Recommended for: Anyone who wants to get better at problem solving, organizational leaders wanting to create a problem solving culture.

From the day I met him, my friend and Lean mentor, Jerry Bussell always recommended using an A3 for the problems I encounter. I ignored him. The A3 was something I didn’t understand during my Lean studies and I had a tendency to gloss over it. During a recent outing, he stressed to me the importance of being a problem solver. I agreed this was something I wanted to improve about myself so decided to give A3 a study and a try.

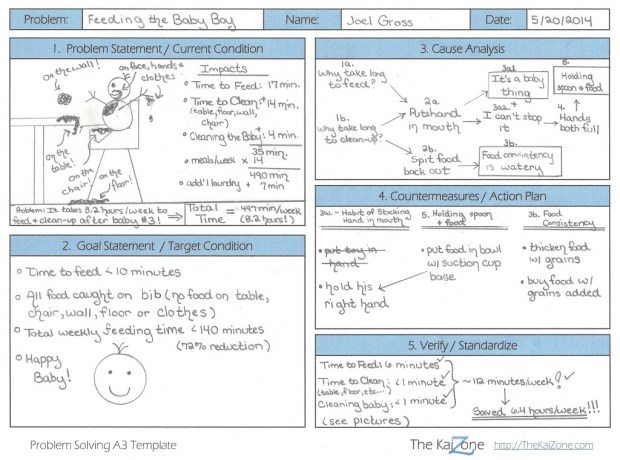

For those that don’t know, the A3 is a Lean tool a person uses who is held responsible for investigating a problem and offering countermeasures. It is typically conducted on an A3-sized paper. Shook’s book is the gold standard for learning the tool.

Example of an A3. Problem– feeding the baby! TheKaiZone,org

This is what I got out it:

- The ultimate goal of the A3 is not to solve the problem at hand, but to make the process of problem solving transparent and teachable in order to create an organization populated with problem solvers (what organization doesn’t want that?).

- The A3 forces you to slow down and think, patiently, instead of just rushing ahead looking for solutions (i.e. firefighter mode). It forces individuals to observe reality, present facts, propose working counter measures designed to achieve the stated goal, gain agreement, and follow up with a process of checking and adjusting for actual results. That’s powerful!

- You must know what the problem is, why its important, and how it ties into what the organization is trying to accomplish. This was an important concept for to me. I think we get so stuck on our solutions, we forget what the problem really is.

- An A3 properly done will produce enemies. (Ouch). This is because as you explore ideas and go into finer details of how people get their work done, the greater degree of turf wars and general push back or resistance you will find.

- Don’t be discouraged. Challenge people with facts, push them to explain their thinking. Refuse sub-optimal results. The more an A3 sparks healthy debate, the more it has done its job.

- Once you complete the process, you will become the company’s expert on the problem. You must then become a champion for getting it implemented or until another course is decided to be taken. This is a great way of gaining influence, I believe.

- A challenge for me– Shook asks, instead of being discouraged by the unending nature of problems cropping up, can you become encouraged by the unending opportunity and challenge?

- Shook recommends using the term ‘countermeasure’ instead of ‘solution’. Countermeasures indicates temporary responses to specific problems where as solutions imply something permanent. Nothing should be permanent. Countermeasures serve until a better approach is found or conditions change.

I am going to try the A3 in the workplace, but I do have concerns:

- The A3 requires patience and understanding. Most American organizations have a culture that values action and decisiveness. When I showed this book to a very trusted and respected colleague of mine, he indicated that it looked like analysis paralysis. Uh oh.

- Nigel Thurlow who is connecting the Agile-Lean divide, believes the A3 is better suited for a linear system, not a complex one, which is what many organizations are facing these days. Thurlow is good friends with Shook; I’d be curious as to what Shook has to think about Thurlow’s opinion on this matter. I’m also curious if Thurlow has an alternative.

This book made me realize I was good at figuring out what was causing problems, but I needed to get better at coming up with countermeasures. It showed me how. I’m looking forward to giving it a whirl.

The book can be ought here.

The Machine that Changed the World

The Machine that Changed the World Orbiting the Giant Hairball

Orbiting the Giant Hairball

My Years with General Motors

My Years with General Motors

Indirectly, Scrum introduced me to W. Edwards Deming. For that, I will always be grateful to it. I’m a big fan of Jeff Sutherland. His book

Indirectly, Scrum introduced me to W. Edwards Deming. For that, I will always be grateful to it. I’m a big fan of Jeff Sutherland. His book  Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us by Daniel Pink

Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us by Daniel Pink

Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance

Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance Its all about getting better results.”

Its all about getting better results.” The World is Flat: A Brief History of the 21st Century by Thomas L. Friedman.

The World is Flat: A Brief History of the 21st Century by Thomas L. Friedman.